Stem Cells In Menstrual Blood Have Potential For Health Advancements, Including Endometriosis Diagnosis

Menstrual stem cells, once overlooked, are emerging as a promising source for significant medical advancements.

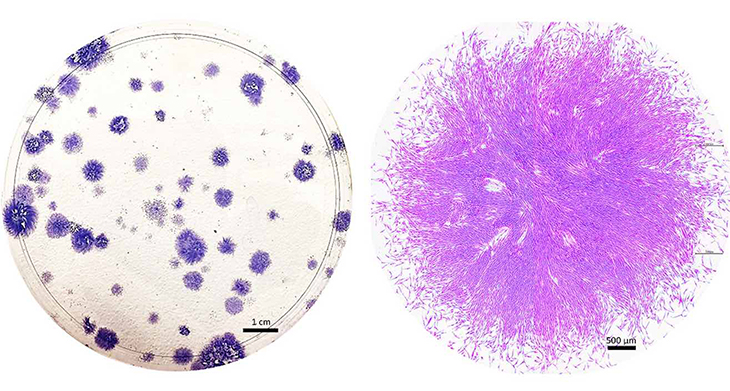

About two decades ago, biologist Caroline Gargett embarked on a quest to uncover remarkable cells within tissue extracted during hysterectomy surgeries. These cells originated from the endometrium, the lining of the uterus. When cultured in a petri dish, they appeared as round clumps enveloped in a pinkish medium.

Under the microscope, she observed two distinct types of cells: one with a flat, roundish shape, and the other elongated and tapered, adorned with whisker-like protrusions. Gargett harbored a strong suspicion that these cells were adult stem cells – a rare and highly esteemed type of cell known for their self-renewing capabilities and ability to differentiate into various tissues.

Gargett and her fellow researchers had long speculated about the presence of stem cells in the endometrium, considering its extraordinary ability to regenerate monthly. This tissue serves as a site for embryo implantation during pregnancy and is subsequently shed during menstruation. Remarkably, it undergoes approximately 400 cycles of shedding and regrowth before menopause sets in.

Gargett explains that while scientists had successfully isolated adults stem cells from various regenerating tissues like bone barrow, the heart, and muscle, “no one has identified adult stem cells in endometrium.”

These cells hold significant value due to their potential to repair damaged tissue and address diseases like cancer and heart failure. However, they are present in limited quantities throughout the body and can be challenging to acquire, often necessitating surgical biopsy or bone marrow extraction with a needle. Gargett expresses that the discovery of a previously untapped source of adult stem cells was exhilarating in itself. Additionally, it presented an exciting opportunity for a fresh approach to addressing long-neglected women’s health conditions such as endometriosis.

These cells are greatly esteemed for their ability to mend damaged tissue and combat diseases like cancer and heart failure. However, they are scarce throughout the body and can pose challenges in procurement, often necessitating surgical biopsy or extraction of bone marrow with a needle. Gargett expresses that the notion of discovering a previously unexplored source of adult stem cells was exhilarating in itself. Furthermore, it sparked the intriguing potential for a fresh approach to addressing longstanding women’s health conditions such as endometriosis.

Before confirming the cells as genuine stem cells, Gargett and her team at Monash University in Australiasubjected them to a battery of rigorous tests. Initially, they assessed the cells’ capacity to multiply and regenerate, observing that some could divide into approximately 100 cells within in a week. Additionally, they demonstrated the cells’ ability to differentiate into endometrial tissue and identified specific characteristic proteins akin to those found in other stem cell types.

Transitioning to her role at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Gargett and her colleagues further characterized various self-renewing cells within the endometrium. Among these, only the whiskered cells, known as endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells, were truly “multipotent,” capable of transforming into fat cells, bone cells, or even smooth muscle cells like those in the heart.

Coincidentally, at the same time, two separate research teams uncovered a surprising revelation: Some endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells were present in menstrual blood.

Gargett found it unexpected that the body would discard such valuable stem cells so readily. Given their critical role in organ survival and function, she initially doubted the body would “waste” them by shedding them. However, she acknowledged the significance of this discovery. Instead of relying on invasive surgical biopsies to obtain the elusive stem cells identified in the endometrium, she realized that they could be collected using a menstrual cup.

Gargett’s team has demonstrated the presence of these specialized stem cells in both the lower and upper layers of the endometrium. Typically enveloping blood vessels in a crescent shape, these cells are believed to aid in vessel formation and play a crucial role in repairing and rejuvenating the upper layer of tissue shed during menstruation.

This layer is indispensable during pregnancy, offering sustenance and support to a developing embryo. Moreover, it seems to be pivotal in infertility issues, as insufficient thickening of this layer can hinder embryo implantation. The endometrial stem cells responsible for its growth play a significant role in this process.

Endometrial stem cells have also been associated with endometriosis, a painful condition affecting approximately 190 million women and girls globally. Although the condition remains poorly understood, researchers speculate that one contributing factor may be the reflux of menstrual blood into a woman’s fallopian tubes. Endometrial stem cells deposited in these regions may prompt the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, resulting in lesions that cause severe pain, scarring, and often infertility.

Scientists are currently in the process of developing a dependable, noninvasive test for diagnosing endometriosis, as patients typically endure an average wait of nearly seven years before receiving a diagnosis.

Nevertheless, research indicates that stem cells extracted from the menstrual blood of women with endometriosis exhibit distinct shapes and patterns of gene expression compared to cells from healthy individuals. Numerous laboratories are actively exploring methods to utilize these variances in menstrual stem cells to identify women at a heightened risk of developing the condition. This advancement holds the potential to expedite diagnosis and treatment procedures.

Moreover, menstrual stem cells may offer therapeutic benefits. Some studies conducted on mice have demonstrated that administering menstrual stem cells into the bloodstream of these animals can facilitate the repair of damaged endometrial tissue and enhance fertility.

Additional research conducted in laboratory animals suggests that menstrual stem cells may hold therapeutic promise beyond gynecological disorders. In several studies, for instance, the injection of menstrual stem cellsinto diabetic mice prompted the regeneration of insulin-producing cells and led to improvements in blood sugar levels. In another study, the treatment of injuries with stem cells or their secretions facilitated wound healing in mice.

Furthermore, a small number of promising clinical trials have demonstrated that menstrual stem cells can be transplanted into humans without adverse side effects.

Gargett’s team is also actively pursuing the development of human therapies. They are utilizing endometrial stem cells obtained directly from endometrial tissue, rather than menstrual blood, to engineer a biodegradable mesh aimed at treating pelvic organ prolapse – a prevalent and painful condition often associated with childbirth.

Despite the convenience of harvesting adult multipotent stem cells from menstrual blood, research exploring and harnessing the potential of these stem cells, particularly in addressing various diseases, remains a relatively small aspect of overall stem cell research.

Daniela Tonelli Manica, an anthropologist that has been leading studies at Brazil’s State University of Campinas, has emerged as a captivating frontier in regenerative medicine, transcending its traditional perception as merely a monthly inconvenience.