Science has evolved since its inception. Even when it began to emerge as a profession, vast changes have been made. Thinkers and physicians in the 18th and 19th centuries had different belief systems then. They claimed that shape of a person’s skull could hold clues to their psychology.

While this belief no longer holds water, this feature in Curiosities of Medical History deserves a more in-depth look. This long-discredited science that is otherwise known as phrenology is extremely interesting, to say the least.

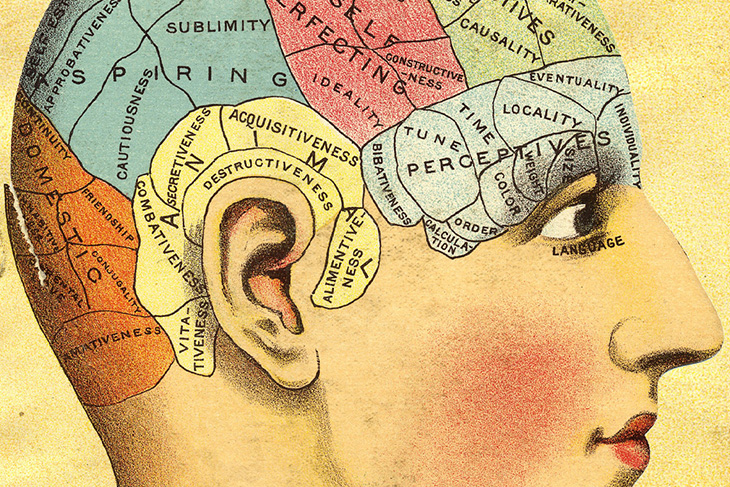

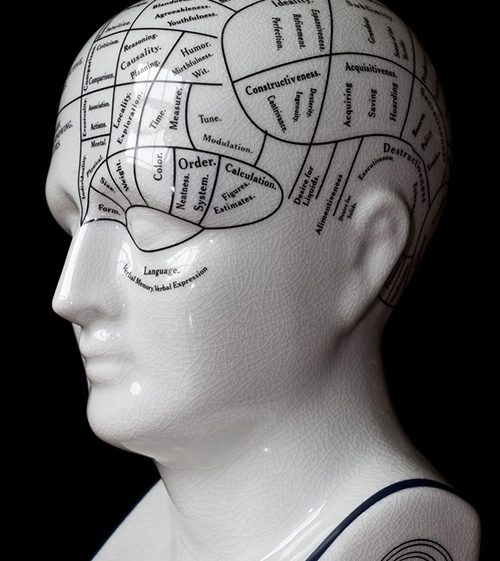

In the 18th century, a new type of science emerged. Phrenology became an interesting study in Europe then. It was once believed that an experienced phrenologist would be able to tell what the psychological inclinations and personality traits of a person simply by feeling the shape of their skull. While doctors at present scoff at the idea, it had been believed to be accurate back then.

The person behind this pseudoscience was a physician named Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828). He says that the shape of a person’s skull gave clues to their personality. Basically, how a person is would be influenced by the shape of his or her skull.

In following years, phrenology evolved. It started to take on a life of its own, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries. People were such staunch believers, and by the land of the latter century, it slowly declined until it died a slow and painless death.

In this Curiosities of Medical History feature, the believers of phrenology had many arguments of their own, but in reality, this pseudoscience was extremely problematic. Still, it did make a significant contribution to the development of neuroscience.

Faculties and Symmetries

The term “phrenology” was not coined by Gall. In fact, the word only came into use later, in the early 1800s. The man behind the word was British physician T.I.M. Forster.

Nonetheless, it was Gall who started and suggested the basis for this science. He wrote, “the possibility of distinguishing some of the dispositions and propensities [of an individual] by the shape of the head and skull.” That was because he firmly believed that not only did the shape of the skull hold clues to a person’s personality and predisposition, but each area of the brain was also linked to different character traits.

Phrenology was applicable to both humans and animals. Gall however believed that humans had more varied mental and emotional capacities. As psychologists Dr. Paul Eling, Prof. Stanely Finger, and Prof. Harry Whitaker wrote in a paper discussing the origin and development of Gall’s ideas: “Gall would ultimately settle for 27 distinct higher functions or faculties of mind {…}. Many of these functions, such as love of offspring and memory for locations, humans share with animals; some functions including wit, poetry, and religion, are uniquely human.”

Some other “faculties” that Gall described are:

- The “instinct of generation, reproduction, or propagation”

- Pride, or “hauteur, loftiness, elevation”

- The memory of things, of facts, “educability, perfectibility”

- Talent for painting

- Talent for music

- The “faculty of the relations of numbers”

- The “faculty of spoken language” or “talent of philology”

Gall also hypothesized that the two hemispheres of the brain were practically interchangeable because both held similar functions. Thus, he says that should one hemisphere sustain damage, the other undamaged portion would be able to compensate.

Parts Performing Distinct Functions

Throughout the 19th century, Gall’s ideas became popular. His beliefs had spread across Europe and North America. What helped him was the series of lectures he gave with his protege, physician Johann Kaspar Spurzheim, by his side. Another reason for its sudden popularity was other adepts of phrenology picked up his thoughts.

One adept was Scottish lawyer and phrenologist George Combe (1788–1858). He who wrote about this pseudoscience in several books, one entitled Elements of Phrenology published in 1824. In this then famous book, Combe lays out the view of how different parts of the brain play a variety of roles. He explains, “The brain, […] being the organ of the mind, the next inquiry is, [w]hether is it a single part, manifesting the whole mind equally, or an aggregate of parts, each subserving a particular mental power? All the phenomena are at variance with the former, and in harmony with the latter, or phrenological, view.” He further argued that “The brain must be a combination of parts performing distinct functions.” Why? He stated five reasons in the published study:

- “[A]ll the powers of the mind are not equally developed at the same time, but appear in succession at different periods of life.”

- A person who has musical talent may not be very skilled at painting, and vice versa, suggesting that different talents “reside” in different parts of the brain, which may be more or less developed.

- “[I]n dreaming, one or more faculties are awake while others are asleep; and if all acted through the instrumentality of one and the same organ, they could not be in opposite states at the same time.”

- Psychiatric issues affect certain behaviors and functions and not others, suggesting that each “faculty” is linked to a different part of the brain.

- “[P]artial injuries of the brain do not equally affect all the mental powers.”

It is believed that Combe was such a believer in the accuracy of phrenology assessments. In fact, he married his wife only after they both underwent an examination to determine their compatibility.

According to Dr. Marc Renneville, a science historian, “Phrenology was at the peak of its popularity in the 1830s,” when people in France, Britain, Spain, Germany, Scandinavian countries, and the United States were talking in-depth and constantly about it. However, Dr. Renneville also says that in the second half of the 19th century, phrenology was on the decline. He writes, “The palpation methods used by phrenologists gradually came to be assimilated with the various divinatory ‘sciences’ practiced by those trading in hopes and promises in the country’s traveling fairs and shows.”

Racist and Sexist Implications of Phrenology

Phrenology had been a topic of interest then. At that time, people were extremely fascinated by it. Although this pseudoscience made contributions to some real scientific progress in understanding how the brain works, it also had discriminatory undertones.

For instance, phrenology studied the differences in men’s and women’s skulls. Hence, both had different mental capacities. The study’s relationship with women was a double-edged sword. While historians say that this “science” was more open to women practitioners, the treatises emphasized the many ways women’s skulls were just different. Ironically, there were more women in this profession than most other scientific fields back then. Its claims remain to be shocking still because there were supposed traits and qualities that were inherent to women, and vice versa.

Orson Fowler (1809–1887), the 19th century American phrenologist says, “[m]en were distinguished by their firmness, force, self-esteem, courage, combativeness, and destructiveness; women were known for exquisiteness, emotion, susceptibility, and ‘devotion to offspring,’ as well as their secrecy, artifice, and nervousness.” This citation was pointed out by historian Dr. Carla Bittel.

Then, there were those who used phrenology as an excuse to explain scientific racism. Simply put, they excused their beliefs to claim that one race is superior to others. In this day and age, this would be considered a great exploitation of science.

In the 19th-century US, for example, a physician named Charles Caldwell (1772–1853) used phrenological beliefs and ideas to support of slavery. He says that individuals of African origin were unequal to Caucasians in their mental constitution. This was based only by the shape of their skulls.

The more contemporary practitioners such as Samuel George Morton (1799–1851) made similar claims to American Indian populations. He used this as a justification to forcefully remove them from their homes, which was originally theirs to begin with.

Legacy for Neuroscience

Phrenology is simply not scientifically viable. However, some of its core ideas did open the doors for progress, especially in the vital field of neuroscience. A good example would be Gall’s ideas on how different parts of the brain were connected to specific functions. This paved the way of a new understanding of how human brain works.

A paper that appeared in the journal Surgical Neurology, Drs. Charles E. Rawlings III and Eugene Rossitch Jr. give credit to Gall because, first and foremost, some of his teachings served as a foundation to brain dissection. He allowed future doctors to closely observe the anatomy of the brain with better accuracy and clarity. They claim, “Almost exclusively, before Gall’s time, [brain] dissection was accomplished by gross sectioning that obviously precluded any substantial tracking of nerves or tracts.” The further explained, “Gall, instead of merely slicing the brain like a melon, would gently tease the fibers of the nerve of tract and follow them to their origin or destination. In this manner, he was able to contribute immensely not only to the anatomic knowledge of the brainstem, but also to neuroanatomy as a whole.”

Many researchers of the brain argue that Gall’s work was pivotal to the discovery of the phenomenon of aphasia. This is an inability or difficulty to understand language or formulate coherent speech due to damage to a specific brain area. With this said, the person most closely linked to the discovery of the brain region tied to language and speech is French physician Paul Broca (1824–1880).

The term Broca’s area came from him. This is the region in charge of speech. He observed this when he studied two patients who had injuries that left them unable to construct sentences.

It is good to note that Broca’s discovery did not happen out of nowhere. His findings were based on existing debates that centered around the localization of speech in the brain. The central figure in this debate was French physician Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud (1796–1881). He had studied Gall’s writings beforehand and wrote a paper about it on February 21, 1825. Bouillaud presented his studies on “Clinical research demonstrating that loss of speech results from a lesion of the anterior lobules of the brain and confirming M. Gall’s opinion on the seat of the organ of articulate language” at the National Academy of Medicine in Paris, France.

Then, there are researchers Drs. Jason W. Brown and Karen L. Chobor. They claim that latter discoveries on the location of the speech function in the brain came from Gall’s original ideas. They say, “We know that the attribution of language to the frontal lobes was derived from Gall’s localization.”

The road to where neuroscience is today had been long, tedious, and extremely controversial. There were convoluted ideas that preceded it, but it did provide further chances for research and investigation on the mysteries of the brain, and that in itself, is worth its mention.