Everyone deals with stress in one way or another. Life’s pressures are inevitable and while stress over a sustained period of time can oftentimes lead to depression, studies on how chronic stress can lead to depression is still very vague.

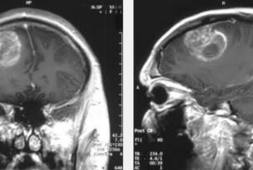

Studies have been made on depression and a recent one shows that individuals who don’t suffer from depression, unlike those with the condition, are able to adapt to elevated everyday stress by changes in the response of the medial prefrontal cortex, the brain region that’s involved in regulating the body’s stress response. They also believe that those who are unable to produce an adaptive and healthy response to elevated everyday stress could actually turn to depression. Moreover, findings may show that the extent of this inability to produce an adaptive response could predict shortcomings in their daily functioning.

There are those who suffer from what experts call major depressive disorder (MDD. This is also known as clinical depression. In reality, this is one of the most common mental health conditions for people in the US. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), around 7.1 percent of adults had gone through a depressive episode in 2017.

Studies have been carried out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on this very issue and the findings suggest how stress of the current COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with an increase in self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms. This is also more common in adults under 30 years of age.

While stress is an everyday occurrence, experiencing this over an extended or prolonged period of time, is linked with the development of depression. This is especially true with the recent and ongoing pandemic. One of the biggest symptoms of depression includes anhedonia. This is the person’s inability to anticipate or feel pleasure when it comes.

However, researchers have still to fully understand how chronic stress eventually leads to depression or the accompanying symptoms of anhedonia. While much has yet to be answered, there are pieces of evidence that suggests that the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), a brain region that is in charge of processing reward and regulating the stress response, could be involved in mediating the accompanying effects of chronic stress.

The mPFC is in charge of regulating the stress response, but both acute and chronic stress could also elicit changes within the mPFC portion of the brain. Researchers have stumbled upon these findings with the studies they performed in rodents. They have shown how glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, is released by neurons in the mPFC in times of acute stress. However, there are rodents who were exposed to chronic stress, and they’ve exhibit lower levels of glutamate release in the mPFC when they were provided with stimulus of a new acute stressful event.

Scientists think that the reduction seen in the mPFC glutamate response due to chronic stress could actually be the body’s protective adaptation to pressure. More importantly, studies had already proven how mPFC glutamate activity is changed in times of depression. Now, a study that was led by a team of researchers at Emory University in the United States shows that people who suffer depression, unlike those who don’t have the condition, are unable to produce an adaptive decrease in mPFC glutamate levels as a response to an increase in daily stress. The extent to which an individual who has depression lacked the important adaptive response predicted their levels of anhedonia in everyday life.

Dr. Jessica Cooper, the study’s first author, explained, “We were able to show how a neural response to stress is meaningfully related to what people experience in their daily lives. We now have a large, rich data set that gives us a tangible lead to build upon as we further investigate how stress contributes to depression.”

The findings of the study itself is found in the journal Nature.

Adaptive Changes in Glutamate Release

To investigate the role of mPFC plays in depression, the researchers recruited around 65 volunteers who don’t suffer from depression. They also got 23 more volunteers who have MDD and who were not taking medication for it.

Then, around 11 to 12 days before the experiment began, the researchers used the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) to measure the participant’s subjective or perceived stress levels over the past month. This was done individually. On the test day itself, the participants were asked to perform and complete a task that induced acute stress. The researchers measured the results with a magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). This is a noninvasive imaging technique that has the ability to measure changes in glutamate levels in the mPFC before and after the acute stress test is made.

The team stumbled upon interesting findings. They observed that the magnitude of change in mPFC glutamate levels due to the acute stress test was linked to the perceived stress levels in people who don’t have depression. Those who don’t suffer from this malady and with lower levels of recent perceived stress, as seen and measured by the PSS, showed an increase in mPFC glutamate levels after the test was done. As opposed to those without depression but with higher perceived stress, they don’t exhibit changes or a decrease in mPFC levels.

While there were changes in mPFC glutamate levels for those with depression during the acute stress test, these observed changes were not linked with their PSS score.

The authors then suggested that the absence of an adaptive change in mPFC glutamate levels may have a vital role in the development of stress-related mental health conditions much like depression.

Depression and Anhedonia

To establish whether the mPFC glutamate response during the acute stress test was linked to daily functioning, the researchers also observed and conducted a survey with the participants with depression every other day after the stress test had been conducted for 4 weeks.

The surveys given were made to check the participant’s optimism or pessimism regarding life activities and the actual outcomes of the activities given. They then used the data gathered and determined the accuracy of the volunteers’ optimistic or pessimistic expectations.

They found that the participants who had MDD were more likely to have more inaccurate pessimistic expectations than those who didn’t have MDD. Then, they created a model using the mPFC glutamate response data that they had gotten from the participants who didn’t have depression. With the results they gathered, they quantified the extent to which the mPFC glutamate response in participants with MDD veered away from those without depression.

The researchers made a score and labeled the quantitative results the maladaptive glutamate response (MGR). The MGR score in participants with MDD was positively correlated with imprecise negative and despairing expectations.

In gist, the extent to which participants with MDD did not exhibit an adaptive decrease in mPFC glutamate levels during acute stress was linked to their inability to expect pleasure, or what they call anticipatory anhedonia.

Limitations and Conclusions

While the authors of the study came up with interesting results, they also acknowledge the fact that the study had its own set of limitations. For instance, as the authors noted, despite their efforts, the range of PSS scores used to estimate perceived stress levels did not extend to people with MDD and those without depression.

They said, “This was not entirely unexpected, as PSS scores are known to be much higher in MDD samples; however, it does limit our ability to determine whether the maladaptive glutamate response we observed was driven primarily by the high severity of perceived stress in MDD, the presence of their current depression, or both.”

With all these in mind, the authors came to a conclusion and said, “These results advance our understanding of the neurobiological adaptation to stress and may play a valuable role in identifying new treatment targets and markers of treatment response in human stress-related illness.”