A groundbreaking study reveals that an African psychedelic plant has made significant strides in alleviating the symptoms of traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) among war veterans. Ibogaine, a naturally occurring compound sourced from the roots of the African shrub iboga, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in enhancing functionality and ameliorating conditions like PTSD, depression, and anxiety in military personnel.

Traditionally utilized in Africa for millennia during spiritual and healing ceremonies, ibogaine has garnered attention for its therapeutic potential without causing adverse side effects, as attested by veterans who underwent experimental treatment and reported life-saving outcomes. In light of the prevalent TBIs among troops deployed in conflict zones like Afghanistan and Iraq, which are often associated with heightened rates of depression and suicide post-deployment, conventional treatment modalities have proven inadequate for a significant subset of veterans.

Ibogaine’s emergence as a promising candidate in scientific circles stems from its capacity to modulate key neurotransmitter systems in the brain, particularly those implicated in addiction and mood disorders. Traumatic brain injury, precipitated by external forces such as explosions or vehicular accidents, engenders structural alterations in the brain architecture, thereby precipitating a spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Recent findings from Stanford Medicine underscore the therapeutic potential of ibogaine, particularly when administered in conjunction with magnesium to safeguard cardiac function. The study, published in Nature Medicineon January 5th, furnishes detailed insights gleaned from a cohort of 30 U.S. special forces veterans, elucidating the compound’s ability to mitigate symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression while bolstering overall cognitive and emotional well-being.

“No other drug has ever been able to alleviate the functional and neuropsychiatric symptoms of traumatic brain injury,” said Nolan Williams, MD. He is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “The results are dramatic, and we intend to study this compound further.”

Since 1970, ibogaine has been classified as a Schedule I substance, barring its usage within the U.S. However, clinics in both Canada and Mexico legally provide ibogaine treatments.

“There were a handful of veterans who had gone to this clinic in Mexico and were reporting anecdotally that they had great improvements in all kinds of areas of their lives after taking ibogaine,” Williams said when he spoke to Stanford Medicine News. “Our goal was to characterize those improvements with structured clinical and neurobiological assessments.”

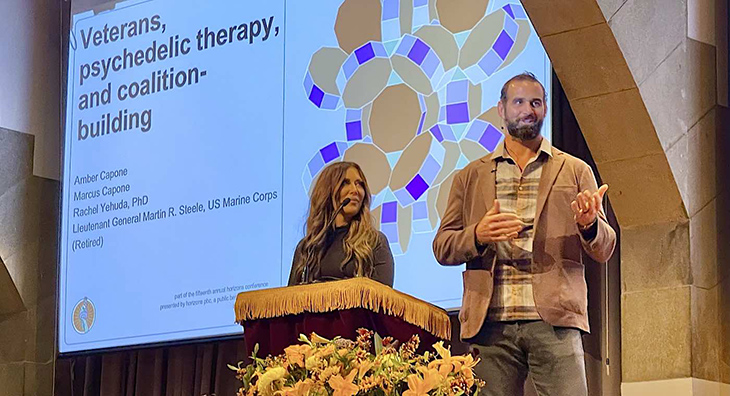

Dr. Williams and his Stanford team collaborated with VETS, Inc., a foundation renowned for its facilitation of psychedelic-assisted therapies for numerous veterans. They recruited 30 special operations veterans, all with a background of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and repeated blast exposures, nearly all of whom were grappling with clinically severe psychiatric symptoms and functional disabilities. These veterans had independently arranged for an ibogaine treatment at a clinic in Mexico before being enlisted for the study.

Prior to the therapy, the researchers assessed the participants’ PTSD, anxiety, depression, and functioning using a blend of self-reported surveys and clinician-conducted evaluations. Subsequently, the participants journeyed to a clinic in Mexico managed by Ambio Life Sciences. There, under medical supervision, they received oral ibogaine supplemented with magnesium to mitigate potential heart-related issues linked to ibogaine. Following the treatment, the veterans returned to Stanford Medicine for follow-up evaluations.

Among the participants, 19 had experienced suicidal ideation, and seven had made suicide attempts.

“These men were incredibly intelligent, high-performing individuals who experienced life-altering functional disability from TBI during their time in combat,” Williams said. “They were all willing to try most anything that they thought might help them get their lives back.”

On average, administration of ibogaine resulted in immediate and substantial enhancements across various domains including functioning, PTSD, depression, and anxiety. These improvements persisted even one month after the treatment, as observed upon conclusion of the study.

Prior to receiving the treatment, veterans exhibited an average disability rating of 30.2 on the disability assessment scale, suggesting mild to moderate impairment. However, following the treatment, this rating dramatically improved to 5.1, indicating a complete absence of disability.

Additionally, one month post-treatment, participants experienced significant reductions in PTSD symptoms by an average of 88%, depression symptoms by 87%, and anxiety symptoms by 81%. Furthermore, formal cognitive assessments demonstrated enhancements in concentration, information processing, memory, and impulsivity among the participants.

“I wasn’t willing to admit I was dealing with any TBI challenges. I just thought I’d had my bell rung a few times—until the day I forgot my wife’s name,” said Craig. He is a 52-year-old study participant from Colorado who was in the U.S. Navy for 27 years.

“Since [ibogaine treatment], my cognitive function has been fully restored. This has resulted in advancement at work and vastly improved my ability to talk to my children and wife.”

“Before the treatment, I was living life in a blizzard with zero visibility and a cold, hopeless, listless feeling,” said Sean. He is a 51-year-old veteran from Arizona with six combat deployments who participated in the study. He talked about how ibogaine saved his life. “After ibogaine, the storm lifted.”

Significantly, ibogaine showed no significant side effects, and notably, there were no reported instances of the heart issues sometimes associated with its use. Among veterans undergoing treatment, the most commonly reported symptoms were headaches and nausea, which are typical and manageable.

Moving forward, the research team intends to conduct additional studies, including an in-depth analysis of brain scans. This examination aims to elucidate the mechanisms through which ibogaine contributes to enhanced cognitive function. Furthermore, the profound impact of ibogaine on traumatic brain injury (TBI) suggests promising therapeutic applications for a wide range of neuro-psychiatric conditions beyond TBI.

“I think this may emerge as a broader neuro-rehab drug,” said Williams. “I think it targets a whole host of different brain areas and can help us better understand how to treat other forms of PTSD, anxiety and depression that aren’t necessarily linked to TBI.”