Scientists Found A Possible Cause For Eczema And This has Led To A Discovery Of A New Form Of Treatment

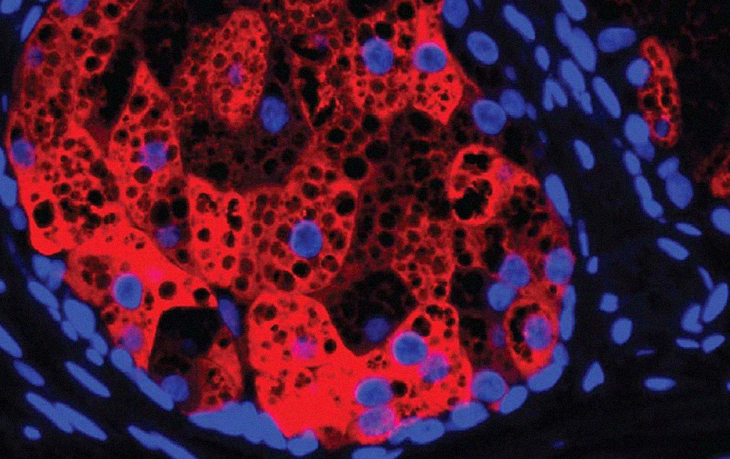

The photo above is a HSD3B1. This red compound is found within a human sebaceous gland cell neclei (blue) and lipid droplets (black circular areas). It was taken by Harris Tyron of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Studies Made

A recent study that was led by UT Southwestern dermatologists suggests that this common inflammatory skin condition otherwise known as eczema may actually come from poorly regulated hormones. Hence, the findings from the said study could offer a new and unconventional target to fight this condition.

In reality, atopic dermatitis (AD) is a form of eczema. This affects up to 13 percent of children and 10 percent of adults. Treatment may vary from simple to elaborate, and the annual treatment has cost as much as $5.3 billion. This figure is a reflection in just the U.S.

“We often think of eczema as a dry-skin condition and treat mild cases with moisturizers,” explained Tamia Harris-Tryon, the corresponding author at UTSW. “Here, we’re showing that a gene that’s important for making hormones seems to play a role in the skin making its own moisturizers. If we could alter this gene’s activity, we could potentially provide relief to eczema patients by helping the skin make more oils and lipids to moisturize itself.”

Dr. Harris-Tryon talked about how previous research has connected AD to overactivity in genes that were in charge of the production of two inflammatory immune molecules, interleukins 4 and 13 (IL-4 and IL-13). With this new revelation, a relatively new drug was made. This is called dupilumab and this is a monoclonal antibody that reduces the amount of the inflammatory molecules. The said treatment has proven to be extremely effective in many patients who suffer from moderate to severe AD. Unfortunately, the molecular mechanisms behind how IL-4 and IL-13 contribute to this form of eczema has yet to be discovered.

Further Investigations

Dr. Harris-Tryon and her colleagues aimed to investigate this question. In order to do so, they honed in on the sebocytes. These are the cells that make up sebaceous glands. These glands produce an oily, waxy barrier that protects and covers the skin in order for it to retain its moisture.

The researchers grew the human sebocytes in petri dishes then dosed these with IL-4 and IL-13. After which, they used a technique called RNA sequencing to get a readout on the gene activity that was happening in the entire genome. They compared the findings with gene activity in sebocytes that weren’t treated with these said immune molecules. It was then that they found that a gene called HSD3B1, which makes an enzyme called 3b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, had become more active, approximately 60 times more when these were exposed to the two interleukins.

The findings made came as a surprise. Dr. Harris-Tryon talked about how they reacted when they saw this. She said that it was because this enzyme was better known for playing a key role in the production of hormones such as testosterone and progesterone. In the past, no scientist had even linked this to atopic dermatitis and skin lipid production.

There were databases made that kept record of human gene activity. These showed that HSD3B1 has the tendency to be overactive especially in those who suffer from eczema. A single study of patients on dupilumab has shown how this drug appears to lower the activity of HSD3B1. Both pieces of evidence in the study suggest that IL-4 and IL-13 can ramp up the activity of this gene.

The researchers manipulated the activity with HSD3B1 in sebocytes growing in petri dishes to see how this gene impacts the sebum output. They found that when they made this gene less active, the hormone levels decreased while the production of skin sebum increased. They did the reverse and found it to be true. Hence, with higher gene activity, this led to higher amounts of hormones and less sebum. The researchers made similar findings in a mouse model of AD. They found that hormone production decreased the production of skin lipids.

Together, Dr. Harris-Tryon said, these findings show how HSD3B1 could actually be the new target. This may be the cure when it comes to fighting AD and potentially other forms of eczema. The details of the research have been published in TNAS.

“Changing the output of this gene could eventually offer a way to treat AD that’s completely different from any treatment that currently exists,” the doctor said. This may actually be one breakthrough that eczema sufferers can finally take comfort in.